Review: ‘Salam – The First ****** Nobel Laureate’ (2018)

Awards are elevated by their winners. For all of the Nobel Prizes’ flaws and shortcomings, they are redeemed by what its laureates choose to do with them. To this end, the Pakistani physicist and activist Abdus Salam (1926-1996) elevates the prize a great deal.

Salam – The First ****** Nobel Laureate is a documentary on Netflix about Salam’s life and work. The stars in the title stand for ‘Muslim’. The label has been censored because Salam belonged to the Ahmadiya sect, whose members are forbidden by law in Pakistan to call themselves Muslims.

After riots against this sect broke out in Lahore in 1953, Salam was forced to leave Pakistan, and he settled in the UK. His departure weighed heavily on him even though he could do very little to prevent it. He would return only in the early 1970s to assist Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto with building Pakistan’s first nuclear bomb. However, Bhutto would soon let the Pakistani government legislate against the Ahmadiya sect to appease his supporters. It’s not clear what surprised Salam more: the timing of India’s underground nuclear test or the loss of Bhutto’s support, both within months of each other, that had demoted him to a second-class citizen in his home country.

In response, Salam became more radical and reasserted his Muslim identity with more vehemence than he had before. He resigned from his position as scientific advisor to the president of Pakistan, took a break from physics and focused his efforts on protesting the construction of nuclear weapons everywhere.

It makes sense to think that he was involved. Someone will know. Whether we will ever get convincing evidence… who knows? If the Ahmadiyyas had not been declared a heretical sect, we might have found out by now. Now it is in no one’s interest to say he was involved – either his side or the government’s side. “We did it on our own, you know. We didn’t need him.”

Tariq Ali

Whether or not it makes sense, Salam himself believed he wouldn’t have solved the problems he did that won him the Nobel Prize if he hadn’t identified as Muslim.

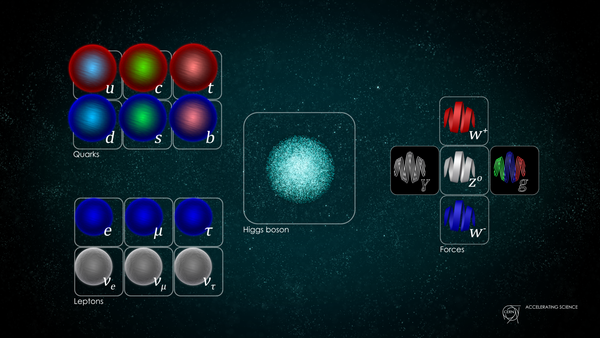

If you’re a particle physicist, you would like to have just one fundamental force and not four. … If you’re a Muslim particle physicist, of course you’ll believe in this very, very strongly, because unity is an idea which is very attractive to you, culturally. I would never have started to work on the subject if I was not a Muslim.

Abdus Salam

This conviction unified at least in his mind the effects of the scientific, cultural and political forces acting on him: to use science as a means to inspire the Pakistani youth, and Muslim youth in general, to shed their inferiority complex, and his own longstanding desire to do something for Pakistan. His idea of success included the creation of more Muslim scientists and their presence in the ranks of the world’s best.

[Weinberg] How proud he was, he said, to be the first Muslim Nobel laureate. … [Isham] He was very aware of himself as coming from Pakistan, a Muslim. Salam was very ambitious. That’s why I think he worked so hard. You couldn’t really work for 15 hours a day unless you had something driving you, really. His work always hadn’t been appreciated, shall we say, by the Western world. He was different, he looked different. And maybe that also was the reason why he was so keen to get the Nobel Prize, to show them that … to be a Pakistani or a Muslim didn’t mean that you were inferior, that you were as good as anybody else.

The documentary isn’t much concerned with Salam’s work as a physicist, and for that I’m grateful because the film instead offers a view of his life that his identity as a figure of science often sidelines. By examining Pakistan’s choices through Salam’s eyes, we get a glimpse of a prominent scientist’s political and religious views as well – something that so many of us have become more reluctant to acknowledge.

Like with Srinivasa Ramanujan, one of whose theorems was incidentally the subject of Salam’s first paper, physicists saw a genius in Salam but couldn’t tell where he was getting his ideas from. Salam himself – like Ramanujan – attributed his prowess as a physicist to the almighty.

It’s possible the production was conceived to focus on the political and religious sides of a science Nobel laureate, but it puts itself at some risk of whitewashing his personality by consigning the opinions of most of the women and subordinates in his life to the very end of its 75-minute runtime. Perhaps it bears noting that Salam was known to be impatient and dismissive, sometimes even manipulative. He would get angry if he wasn’t being understood. His singular focus on his work forced his first wife to bear the burden of all household responsibilities, and he had difficulty apologising for his mistakes.

The physicist Chris Isham says in the documentary that Salam was always brimming with ideas, most of them bizarre, and that Salam could never tell the good ideas apart from the sillier ones. Michael Duff continues that being Salam’s student was a mixed blessing because 90% of his ideas were nonsensical and 10% were Nobel-Prize-class. Then, the producers show Salam onscreen talking about how physicists intend to understand the rules that all inanimate matter abides by:

To do this, what we shall most certainly need [is] a complete break from the past and a sort of new and audacious idea of the type which Einstein has had in the beginning of this century.

Abdus Salam

This echoes interesting but not uncommon themes in the reality of India since 2014: the insistence on certainty, the attacks on doubt and the declining freedom to be wrong. There are of course financial requirements that must be fulfilled (and Salam taught at Cambridge) but ultimately there must also be a political maturity to accommodate not just ‘unapplied’ research but also research that is unsure of itself.

With the exception of maybe North Korea, it would be safe to say no country has thus far stopped theoretical physicists from working on what they wished. (Benito Mussolini in fact setup a centre that supported such research in the late-1920s and Enrico Fermi worked there for a time.) However, notwithstanding an assurance I once received from a student at JNCASR that theoretical physicists need only a pen and paper to work, explicit prohibition may not be the way to go. Some scientists have expressed anxiety that the day will come if the Hindutvawadis have their way when even the fruits of honest, well-directed efforts are ridden with guilt, and non-applied research becomes implicitly disfavoured and discouraged.

Salam got his first shot at winning a Nobel Prize when he thought to question an idea that many physicists until then took for granted. He would eventually be vindicated but only after he had been rebuffed by Wolfgang Pauli, forcing him to drop his line of inquiry. It was then taken up and to its logical conclusion by two Chinese physicists, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang, who won the Nobel Prize for physics in 1957 for their efforts.

Whenever you have a good idea, don’t send it for approval to a big man. He may have more power to keep it back. If it’s a good idea, let it be published.

Abdus Salam

Salam would eventually win a Nobel Prize in 1979, together with Steven Weinberg and Sheldon Glashow – the same year in which Gen. Zia-ul-Haq had Bhutto hung to death after a controversial trial and set Pakistan on the road to Islamisation, hardening its stance against the Ahmadiya sect. Since the general was soon set to court the US against its conflict with the Russians in Afghanistan, he attempt to cast himself as a liberal figure by decorating Salam with the government’s Nishan-e-Imtiaz award.

Such political opportunism contrived until the end to keep Salam out of Pakistan even if, according to one of his sons, it “never stopped communicating with him”. This seems like an odd place to be in for a scientist of Salam’s stature, who – if not for the turmoil – could have been Pakistan’s Abdul Kalam, helping direct national efforts towards technological progress while also striving to be close to the needs of the people. Instead, as Pervez Hoodbhoy remarks in the documentary:

Salam is nowhere to be found in children’s books. There is no building named after him. There is no institution except for a small one in Lahore. Only a few have heard of his name.

Pervez Hoodbhoy

In fact, the most prominent institute named for him is the one he set up in Trieste, Italy, in 1964 (when he was 38): the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics. Salam had wished to create such an institution after the first time he had been forced to leave Pakistan because he wanted to support scientists from developing countries.

Salam sacrificed a lot of possible scientific productivity by taking on that responsibility. It’s a sacrifice I would not make.

Steven Weinberg

He also wanted the scientists to have access to such a centre because “USA, USSR, UK, France, Germany – all the rich countries of the world” couldn’t understand why such access was important, so refused to provide it.

When I was teaching in Pakistan, it became quite clear to me that either I must leave my country, or leave physics. And since then I resolved that if I could help it, I would try to make it possible for others in my situation that they are able to work in their own countries while still [having] access to the newest ideas. … What Trieste is trying to provide is the possibility that the man can still remain in his own country, work there the bulk of the year, come to Trieste for three months, attend one of the workshops or research sessions, meet the people in his subject. He had to go back charged with a mission to try to change the image of science and technology in his own country.

In India, almost everyone has heard of Rabindranath Tagore, C.V. Raman, Amartya Sen and Kailash Satyarthi. One reason our memories are so robust is that Jawaharlal Nehru – and “his insistence on scientific temper” – was independent India’s first prime minister. Another is that India has mostly had a stable government for the last seven decades. We also keep remembering those Nobel laureates because of what we think of the Nobel Prizes themselves. This perception is ill-founded at least as it currently stands: of the prizes as the ultimate purpose of human endeavour and as an institution in and of itself – when in fact it is just one recognition, a signifier of importance sustained by a bunch of Swedish men that has been as susceptible to bias and oversight as any other historically significant award has been.

However, as Salam (the documentary) so effectively reminds us, the Nobel Prize is also why we remember Abdus Salam, and not the many, many other Ahmadi Muslim scientists that Pakistan has disowned over the years, has never communicated with again and to whom it has never awarded the Nishan-e-Imtiaz. If Salam hadn’t won the Nobel Prize, would we think to recall the work of any of these scientists? Or – to adopt a more cynical view – would we have focused so much of our attention on Salam instead of distributing it evenly between all disenfranchised Ahmadi Muslim scholars?

One way or another, I’m glad Salam won a Nobel Prize. And one way or another, the Nobel Committee should be glad it picked Salam, too, for he elevated the prize to a higher place.

Note: The headline originally indicated the documentary was released in 2019. It was actually released in 2018. I fixed the mistake on October 6, 2019, at 8.45 am.